This post assumes basic familiarity with Turing machines, P, NP, NP-completeness, decidability, and undecidability. The reader is referred to the book by Sipser, or the book by Arora and Barak for any formal definitions that have been skipped in this post. Without further ado, let’s dive in.

Introduction

Preliminaries: Search and Decision Problems

In an earlier post, we familiarised ourselves with the notion of reductions . Towards the end, we introduced the notion of self-reducibility which is our main topic of focus today. We start by familiarising ourselves with a few concepts.

In the world of complexity and computability, a language is a set of strings formed out of some alphabet. Formally,

Last time we formalized reductions in terms of Turing Machines

. We now explicitly define mapping reductions (equivalent to Karp reductions for TMs) in terms of languages. Let

A decision problem is a Boolean-valued function

Recall that complexity classes P and NP are defined w.r.t. decision problems.

In complexity theory, many problems can be naturally expressed as search problems (for example, TSP, HamCycle, etc.), but are shoehorned into the above model of decision problems in order for us to easily classify them into classes like P and NP.

Search Problems: A search problem is a relation

A Turing machine

We remark here that a relation

Since the complexity class NP is defined w.r.t. decision problems, we need to introduce an equivalent notion for search problems. Informally, this is denoted by the class FNP (or Function NP). (We make this informal connection explicit shortly.)

A relation

Formally, a polynomially-balanced relation

A search problem

Note that FP is analogous to P in the context of search problems. The following theorem cements this analogy.

FP = FNP iff P = NP.

Search-to-Decision reductions

Recall that decision problems answer the following flavour of questions:

Given a problem

, is a solution to ? (Yes/No).

On the other hand, search problems answer the following flavour of questions:

Given a problem

, output a solution to (preferably with some constraints on the solution).

For example, given a problem

We use the satisfiability problem (SAT) and its search version (FSAT) as an example to further illustrate the two notions:

- Decision problem: Given a propositional formula

SAT) - Search problem: Given a propositional formula

FSAT)

It is straightforward to see that if it is easy to solve the Search version of a problem

Can we efficiently solve the Search version of a problem

, if we know how to solve the Decision version of efficiently?

A problem is self-reducible or auto-reducibile if it admits an efficient search-to-decision reduction, i.e., any efficient solution to the decision version of the problem implies an efficient solution to the search version of the problem.

In this section, we see some examples of search-to-decision reductions / self-reducibility. Let us start with designing a search-to-decision reduction using SAT and FSAT, which are NP-complete and FNP-complete problems respectively.

Search-to-Decision Reduction for SAT

Formally, let

There are two inputs to the FSATSearchToDecision() reduction

- the propositional formula

f, and - the decision oracle for SAT on

DSAT(f,assign)which takes as input a propositional formulafand a restricted assignmentassignand returns yes ifffis satisfiable under the restrictionassign. The output of theFSATSearchToDecision()procedure is a satisfying assignment forf).

FSATSearchToDecision(f,DSAT()){

assignarr = [*,*,....,*];// Intitalize assignarr as an n-bit empty array.

if(DSAT(f,assignarr)=0) // is f satisfiable without restrictions?

return -1; // f is not satisfiable

for (i=1;i<=n; i++){

assignarr[i]= 0

//Fix the ith bit in x to be 1.

// This fixes the ith literal in f.

if (DSAT(f,assignarr)==1)

continue;

// move on to the i+1th coordinate,

// with the ith bit set to 0.

assignarr[i]= 1

//Fix the ith bit in x to be 0.

// This fixes the ith literal in f.

if (DSAT(f,assignarr)==1)

continue;

// move on to the i+1th coordinate,

// with the ith bit set to 1.

return assignarr;

}

Search-to-Decision Reduction for CLIQUE

Earlier we saw that the property used by the decision oracle was a restricted assignment. We list another example of a search-to-decision reduction for the Clique problem (another one of Karp’s original 21 NP-complete problems), to give a flavour of a different decision oracle property - based on size.

- The Clique Decision problem: Given a graph

- The Clique Search problem: Given a graph

As seen above, there are two inputs to the CliqueSearchToDecision() reduction:

- the graph

L, and - the decision oracle for Clique on

DCLIQUE(L,k)which takes as input a adjacency listLand a parameterkand returns yes iff the graph corresponding toLcontains a clique of size at mostk. The output of theCliqueSearchToDecision()procedure is an adjacency list corresponding to a clique in

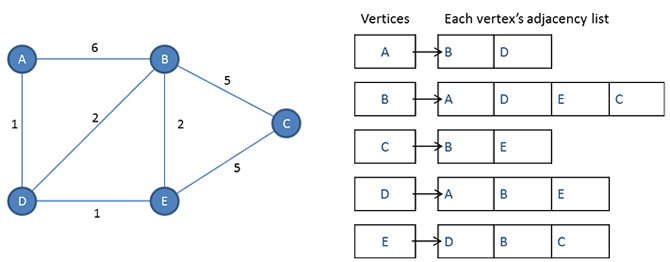

Recall that an adjacency list is a collection of unordered lists used to represent a finite graph. We use the following definition of adjacency lists (this is a modification of the definition given in CLRS): An adjacency list is a singly linked list where each element in the list corresponds to a particular vertex, and each element in the list itself points to a singly linked list of the neighboring vertices of that vertex. See the diagram below.

CliqueSearchToDecision(L,DCLIQUE()){

if(DCLIQUE(L,k)=0)

return -1; // There is no clique of size at most k

for every vertex v of G {

Let Lv be the new adjacency list

obtained by removing vertex v from G.

// easily done using the above datastructure.

if(DCLIQUE(Lv,k)=1)

L = Lv; // update the graph to reflect G = G-v.

}

return L;

}

Downward-self-reducibility

A related concept to self-reducibility is the notion of downward-self-reducibility. Broadly speaking, self-reducibility asks the following question:

Can we solve a search problem

if we can solve under certain constraints?

Earlier, we required that the constrained version of the search problem

Can we solve a search problem

where solutions belong to the domain , if we can efficiently solve under ?

This is still an interesting question, since we note that the optimal solution to

Downward-self-reduciblility for Search Problems

A search problem

In other words, a language

Before we dive deeper into this topic, we digress and familiarise ourselves with a similar notion for decision problems - this helps us ask analogous questions, and establish parallels between search and decision versions of downward-self-reducibility.

< Start of Digression >

Downward-self-reduciblility for Decision Problems

We can extend the notion of downward self-reducibility to functions or decision problems as follows: A function

It is easy to see that SAT is d.s.r. (in the decisional sense) since given any formula FSAT can be shown to be d.s.r. (in the search sense) by using the downward-self-reducibility of SAT.

All NP-complete decision problems are downward-self-reducible.

Proof Sketch. First we show that SAT is d.s.r. This is easy to do since using a construction similar to the above construction that showed FSAT to be self-reducible. For any arbitrary NP-complete problem, we now use the fact there exists a polynomial-time reduction from SAT.

Are all problems in NP (not necessarily complete) downward-self-reducible?

Again, suprisingly the answer to this question is not known to be true!! While the answer is known to be true for problems in P and all NP-complete problems, there are certain barriers to showing that the answer to the above question is true.

In fact, any answer to this question seems to have deep connections with Ladner’s Theorem which posits the existence of the NPI (NP-intermediate) class if P

We shall dwell on this question in more detail in the next post . For now, we briefly turn our attention away from the P-NP hierarchy and onto larger complexity classes. We know that the polynomial hierarchy is not known to have complete problems (this would have serious complexity theoretic implications1), but we know that every level in PH admits complete problems.

For any arbitrary

, consider any problem that is complete for the th level of the Polynomial Hierarchy. Is is downward-self-reducible?

Using arguments similar to SAT, one can show that Quantified Boolean Formulas are, the question seems to be open in full generality2. What about problems beyond the Polynomial Hierarchy? How high can we go before we encounter a barrier to downward-self-reducibility?

Every downward self-reducible decision problem is in PSPACE.

Proof. Let the input to a d.s.r. problem

Recall that PSPACE is closed 3 under Karp-reductions. Since, all d.s.r. languages belong to PSPACE, we can conclude that PSPACE is hard in any sense (for example, worst-case or average-case) if and only iff a d.s.r. language is hard in the same sense.

An application: Mahaney’s Theorem

A language

[Mahaney’s Theorem] Assuming P

NP, there are no sparse NP-complete languages.

Proof Sketch: Recall the d.s.r tree of SAT. Given a SAT formula

The above proof sketch is due to Joshua Grochow4, who credits Manindra Agrawal for the original idea. See Oded Goldreich’s comments here . Due to the lack of formatting in the above linked blog (and for my own archival purposes), I reproduce his comments as-is below.

Oded’s comments: The proof is indeed simple, not any harder than the proof that assumes that the sparse set is a subset of a set in P (see Exercise 3.12 in my computational complexity book).

The first idea is to scan the downwards self-reducibility tree of SAT and extend at most polynomially many viable vertices at each level of the tree, where this polynomial is determined by the polynomials of the sparseness bound and the stretch of the Karp-reduction (of SAT to the sparse set). The crucial idea is the following: Rather than testing the the residual formulae at the current level by applying the Karp-reduction to each of them, one applies the Karp-reduction to the disjunction of the first formula (i.e.,

) and each of the remaining formulae (i.e, the ’s for ). The point is that if all reduction values are distinct, then one of these values is not in the sparse set, and it follows that the first formula is not in SAT, and so the first formula can be discarded. Otherewise, if the reduction maps

and to the same value, then we can discard (say) , since either is in SAT (and remains viable) or is not in SAT and so and have the same SAT-value (and so it suffices to keep either of them).

< End of Digression >

Downward-self-reduciblility and Self-reducibility for Search Problems (Continued)

Earlier we saw that all NP-complete decision problems are downward self-reducible. We also saw a notion of equivalence between the complexity classes P

Are all FNP-complete problems downward-self-reducible?

Surprisingly, the answer to this question is not straightforward unlike its decisional version!

Consider any

On this note, one might ask for a characterization of search problems that are downward-self-reducible? Once again, the answer to this question is discussed in detail in the next post .

Since downward-self-reducibility seems to be untenable for search problems, we turn our attention to self-reducibility for search problems. In that same vein, one might be tempted to raise the following question:

Is every problem in FNP self-reducible?

In other words, if a search problem admits efficiently verifiable solutions, does it admit efficient search-to-decision reductions?

At first glance, this question might make sense since we are no longer worried about the structure of the output string, at least on the surface! Above, we saw examples of NP/FNP-complete problems admitting efficient search-to-decision reductions where both the search and decision verions are computationally hard. On the other hand, Maximum Matching and Shortest Path are problems where both the search and decision versions are computationally easy, and hence admit efficiently constructible search-to-decision reductions by definition.

Since these two categories of problems (P

Surprisingly (or not) that answer is no! While, some problems have naturally equivalent notions of search and decision problems, for others search and decision problems may not be computationally equivalent. This brings us to the following question:

Which search problems are (not) known to be self-reducible?

We try to answer this question in our next post . Minor spoiler alert: A completely unconditional answer is a major open question.

Footnotes

See this StackExchange answer , and this blog post by Gil Kalai on the Aaronson-Arkhipov result . Bonus: See this satirical writeup by Scott Aaronson . ↩︎

I am personally unaware of an answer to this question. Please reach out to me if you have any resources that address / even discuss this question and I will be happy to add it to the blog (with credits). ↩︎

We recall the notion of notion of complete problems here. ↩︎