This post assumes basic familiarity with Turing machines, P, NP, NP-completeness, decidability, and undecidability. The reader is referred to the book by Sipser, or the book by Arora and Barak for any formal definitions that have been skipped in this post. Without further ado, let’s dive in.

Introduction

The What and Why of reductions?

From Archimedes terrorizing the good folk of ancient Syracuse to Newton watching apples fall during a medieval plague, science has always progressed one ‘Eureka!’ at a time. Romantic as these anecdotes may be, for mathematics, we can hardly look to Mother Nature for providing us the key insight to our proofs. Therefore, we must develop principled approaches and techniques to solve new and unseen problems. Here is the good part:

Most unsolved problems we encounter are already related to some existing problem we know about.

This relation to solved problems is something that we can now prod and prick incessantly and eventually use to arrive at a conclusion about new problems. While hardly elegant in its conception, this approach is highly sophisticated in its execution. This is the basis for the mathematical technique known as reduction.

When can we use reduction techniques?

First we start by describing two types of problems: hard and easy! Hard problems are typically those that the problem solver does not know how to solve or knows are very hard to solve, while easy problems are simply easy to solve.

Since the notion of hardness as described above is quite subjective and non-rigorous, we formalize it below by quantifying the capabilities of the problem solver.

Throughout this post, we assume that the notion of hard and easy depends only on the computational resources available to the problem solver.

Access to powerful computational models might allow us (the problem solver) to efficiently find solutions to previously hard-to-solve problems. For example, SAT can be easily solved if we have know how to solve the Halting problem. We shall expand on this example later in this post

.

Take two problems1,

Case 1:

In this case, mathematically, we say that

Reducing problem

to is the process of transforming instances of into instances of . Note that this is only possible if .

Case 2:

In this case, we can again exploit the structural similarities between

We start with the assumption that

Since

Let us explore a few properties of reductions now.

Relative Hardness

For any pair of languages / decision problems

Reductions as relations

- Reflexivity of reductions: Trivially

- Transitivity of reductions: If

- Reductions are, however, not symmetric relations (and, therefore, by extension, not equivalence relations).

A concrete example of this will be discussed later in detail: We can reduce SAT, which is a decidable problem, to the Halting problem, which is an undecidable problem, but the converse is not true (by definition of decidability).

An alternate view of reductions

Reductions are a highly general family of techniques, and to provide a rigorous formalization of reductions, we consider some specific variants. An interesting way of looking at reductions is as follows:

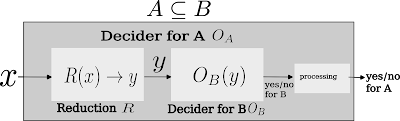

Given an oracle for a problem

, can we solve efficiently by making oracle calls to ? If yes, then .

Here, an oracle is nothing but a black-box subroutine for efficiently solving a problem. The beauty of reductions lie in the fact that we do not need to bother about the internal mechanisms of the oracle itself. Nor do we have to worry about construct the oracle itself. We simply have to use the oracle’s existence. Implicitly, reduction is a two-step process. Suppose

- Suppose there exists a subroutine

- Next, we perform invocation(s) to the oracle for

The notion of efficiency is twofold.

Firstly, we are concerned with how efficient the transformation/reduction from

- Only the construction of the reduction method

- Only the construction of the reduction method

Sometimes, we might require more than one call to the oracle

We explore the notion of efficiency in reductions via an example.

Example of an “efficient” reduction

Consider the following C pseudocode:

int A(int x){ for(;x>12;x++); return x; // This is R(x) }- Writing this piece of code took finite time, and was certainly efficient. However, depending on the value of the input the

forloop will never terminate for values ofA, and not how efficientlyAtransforms

- Writing this piece of code took finite time, and was certainly efficient. However, depending on the value of the input the

A Prototypical Reduction: SAT to the Halting Problem

Note: This is a highly technical section, and would need familiarity to the satisfiability problem and the Halting problem. We encourage the reader to familiarize themselves with the formal definitions of these problems first before going through this section. We give an intuitive description of the problems below.

The Halting Problem

Recall the earlier piece of pseudocode with a slight modification.

int A1(int x){

for(;x>12;x++);

return x; // This is R(x)

}

int A2(int x){

for(;x>12;x--);// This loop will always terminate

return x; // This is R(x)

}

Note A2 will always halt no matter the input, while A1 may never halt depending on the input.

Imagine you would like to design a function

The Halting problem (HALT): Given (the binary encoding of) any arbitrary Turing Machine

and an arbitrary input (encoded as a binary string) , does halt?

This in effect describes the Halting problem, where

The SAT Problem

A Boolean formula

The satisfiability(SAT) problem: Given a Boolean formula

and an arbitrary bit string , is ?

Note that the structure of SAT is subsumed by the structure of the Halting problem. If the decider to Halting problem ever halts, we can find out whether

Even though SAT can be quite hard to solve computationally (may have exponential runtime depending on the structure of the formula), we can always construct an algorithm to solve it. Therefore, right off the bat, we observe that SAT is easier to solve (it is decidable) than the Halting problem.

Reducing SAT to HALT

Let us finally have a look at how we would reduce SAT to the Halting problem.

Our input

We construct a TM (Turing Machine)

🔴 This may require exponential runtime in the size of the formula.- If

🟣 Hence, if x is satisfiable, T halts.

- If

Otherwise, we put

🟣 Hence, T halts iff if x is satisfiable.

Our reduction

🟣 Note that $R(x)$ at this point can be compared to a compiled binary which has not yet been executed.We pass

- If

- If

- If

Once again we note the following (recall this ).

In step 2, we are simply constructing the TM

, not executing it. Think of this as writing a C or Java program/executable for . However, we are never actually going into runtime; i.e. executing the executable at any point.

The reduction is the transformation of the SAT formula

Taxonomy of Polynomial-time reductions

In this post, we only consider polynomial-time deterministic reductions, i.e.,

- the time taken to transform

- the number of calls to

are both polynomial. These are the most commonly studied types of reductions,2 and we look at three kinds of polynomial-time reductions.

Karp Reductions / Many-one reductions

These are the most restrictive type of polynomial reductions.

Given a single input SAT to HALT was a Karp reduction.

We can choose to strengthen the notion of Karp reductions to include weaker forms of reductions.

For example, in logspace many-one reductions, we can compute

Truth Table Reductions

These are reductions in which given a single input

Let us assume that

outputs for the desired combination and otherwise. Here, is efficiently computable, and there are a constant ( ) number of oracle calls to .

Let us consider an example. Consider two problems on a graph

: What is the minimum sized independent set for ? : Does have an independent set of size ?

The reduction

Cook Reductions / Poly-time Turing Reductions

Here, we are allowed a polynomial number of oracle calls and polynomial time for transforming the inputs. These are the most general form of reductions, and the other forms of reductions are restrictions of Cook reductions. In the example graph

where, denotes Karp reductions, denotes Truth Table reductions, and denotes Cook reductions.

Aside: From the nature of the examples, we can see that Karp reductions only extend to decision problems (problems with yes/no outputs). In contrast, Cook reductions can accommodate search/relation/optimization problems (problems with a set of outputs).

Basic reductions in Computability Theory

In this section, the reader is assumed to have familiarity with concepts of decidability and undecidability. Let us now proceed with some instances of reductions in computability theory.

Let

- If

- If

- If

We know that

The third case is of interest here - To show that a

Now again, consider

- If

- If

- If

- If

The first two statements are true, as discussed above, while 3 is the contrapositive of the first statement and the fourth statement is the contrapositive of the second statement. For the fifth statement, the proof is as follows:

. Therefore, .

Immediately we see the power of formalizing the notion of reductions.

Complexity-Theoretic notions

This section is for advanced readers only due to the number of prerequisites involved.

A complexity class is a set of computational problems that can be solved using similar amounts of bounded resources (time, space, circuit depth, number of gates, etc.) on a given computational model (Turing machines, circuits, cellular automaton, etc.).

The complexity classes

We now explore two interesting notions in complexity theory that arise from reductions.

Completeness

For a bounded complexity class,

Complete problems are the hardest problems inside their respective complexity class.

A more formal definition of completeness is as follows:

Given a complexity class

which is closed under reduction , if there exists a problem in such that all other problems in are -reducible to , is said to be C-complete.

For example, an NP-complete problem is in NP, and all problems in NP are Karp-reducible to it. The notions of PSPACE-completeness and EXPTIME-completeness are similarly defined under Karp-reductions.

The role of reductions in this context can be understood through P-completeness. Consider any non-trivial decision problem in P (trivial problems are akin to constant functions). Every other non-trivial decision problem is Karp-reducible to it. Therefore every non-trivial decision problem is P-complete under Karp-reductions. This definition is essentially the same as P (minus the empty language and

Therefore, we come to the following conclusion:

Under Karp-reductions, the notion of P-completeness is semantically useless.

Hence, we use weaker forms of reductions such as logspace reductions or reductions using constant depth circuit computable functions to achieve a more meaningful notion of P-completeness 3.

Self reducibility

Decision problems are yes/no problems where we ask if a solution exists. However, sometimes we also want to solve the corresponding search problem to find a solution (if one exists).

In the context of languages in NP, self-reducibility essentially states that if we can efficiently solve the decision version of a problem, we can also efficiently solve the search/optimization version of the problem. A more formal definition would be as follows:

The search version of a problem Cook-reduces (polynomial-time Turing-reduces) to the decision version of the problem.

Fact: Every NP-complete problem is self-reducible and downward self-reducible4.

Conclusion

This write-up aims to demystify a core technique used in theoretical computer science and provide a few contexts for its usage. For a more rigorous and formal introduction to this topic, please check out Michael Sipser’s excellent book “An Introduction to the Theory of Computation.” There are many more things to say about reductions, and this article barely scratches the surface on any of the topics it touches. However, I feel it would be prudent to stop at this point before it becomes any more of a rambling mess than it already is.

Formally, we consider problems

We will look at the notion of randomized reductions in another post. ↩︎

We will look at weaker notions of reductions in another post. ↩︎

We will look at the notions of self-reducibility and downward self-reducibility in another post . ↩︎